The first time I recognized I had the “H-factor” as a young Yoruba woman was in an English language class in my senior year of secondary school. I’m not sure who first used this term or how they came up with it, but that’s what they call it. Perhaps on purpose, our teacher had called out terms for us to spell correctly in our notebooks; words like eight, ate, hate, hair, air, hear, and ear, to mention a few. I was convinced I would ace the test, but not until he started to make corrections and I was puzzled. I had gotten almost everything wrong, and I could not understand why or how, until my classmate, Ronke, pointed out to me that we had heard wrongly because we had the ‘H-factor’. Ronke had, in fact, scored ten out of ten. English major in the actual mud.

As a non-Nigerian (non-Yorubas should understand what this means, but for those who do not), having the ‘H- factor’ as a Yoruba person means you put the alphabet H anywhere you find a vowel. This means I could tell someone ‘I have an earache’ and the person would hear ‘Hi have an hear hache’. Sometimes, it could be one misplaced H, meaning I insert the H where it shouldn’t be and remove it from its proper location. Other times, the H is before every vowel in the sentence.

An example is trying to say ‘How are you doing today? Is your child okay?’ and the recipient would hear ‘Ow are you doing today? His your child hokay?’.

Either way, as a Yoruba descendant, you cannot escape it. Except you are lucky, very lucky. But I don’t think it’s luck. Your parents probably took you to the river to cleanse your tongue as a baby, or you are a special one the gods have chosen to cherish, nurture, and love, and exempt from this ‘thing’.

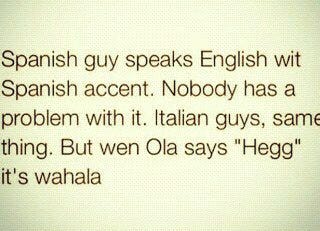

A few years back, I came across the image below on the internet, and it got me thinking. Everyone has an accent, so why am I so self-conscious about mine?

The issue of double standards creeps in and I think it needs to be checked. For instance, we adore the French and the Italians for their strong accents, but a Nigerian’s accent is an issue. And the H factor is where we draw the line?

I no longer speak in this manner (at least, I make an effort not to, and might I add how difficult it is), but occasionally it still comes out of me like a caged monkey who refuses to stay in its cage but wants to go outside and play. However, this monkey is ignorant of the fact that doing so may be embarrassing.

You also find this play out in the way Yorubas spell their names, at least for fun or for the most part, I suppose as a joke because I don’t want to believe there is any way a person would spell out their name as so. For example, my name is Oluwatobi Ojenike. A Yoruba person (again for fun, I emphasize) would probably spell it as Holuwatobi Hojenike. It could also be written as Horluwatobi Horjenike.

When this trend broke out on Facebook a handful of years ago, it left me more puzzled than amused.

Why?

That was my question.

I never understood it.

As I type this, the most pressing issue on my mind is, “How did this come to play?” How did we obtain the H factor and where did it come from? Almost every Yoruba person I know has it, with the exception of those who were born and bred outside of Nigeria. This is not to suggest that it is an illness or a pandemic. As only Yorubas possess it, we are unable to claim that it is Nigerian. I’m not sure if I’ve ever met an H-factor Igbo, Hausa, Fulani, or Kalabari person. Not that they don’t have their own “factors,” mind you. They do, to the best of my knowledge.

So I ask, how did the H-factor come to be? Where did it begin? Who was the first to encounter it? Were they taken aback? Did the first person to hear them speak believe it was the “H factor” or that the gods were mad at the person and were about to drive them crazy?

I was motivated to write this after seeing a tweet from a while back—roughly a year ago if I remember correctly. The person who tweeted it said they were talking to someone and the ‘H factor’ that they tried so hard to suppress jumped out. The handle ended the tweet with ‘Oduduwa please.’

Traditionally, Oduduwa was a Yoruba ancestor and deity. So when I saw the tweet, I instantly related to it as a Yoruba lady.

I recently learned that if I tried to speak more slowly, as it is with speaking in general, I would not encounter this "problem". But, why should I be restrained in my speech because my ancestor has refused to leave my tongue alone?

Again, Oduduwa, please!

Comments

Post a Comment